“Why are you carpet-cleaning the flowerbeds?” is the question most commonly directed at Jonathan Greatrex and his team at the Glamorgan Council parks department.

And visitors can be forgiven for their confusion. The Foamstream machines, now in use across the council’s parks, do for all the world look like carpet shampooers.

But they’re actually part of a move to clean up in a different way: by doing away with potentially dangerous weedkillers.

Concern about glyphosate – the world’s most widely-used weedkiller – has been growing since 2015, when the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) said it was probably carcinogenic.

Since then, tens of thousands of plaintiffs have joined lawsuits against German chemical giant Bayer, claiming that its glyphosate-based weedkiller Roundup has given them cancer.

In the EU the use of glyphosate is currently approved until 2022. However, Germany, Austria, Italy, the Netherlands, France and the Czech Republic are all promising or considering bans.

And with the tide turning against glyphosate, many organisations that routinely battle weeds are turning to some decidedly unconventional alternatives.

In the case of Foamstream, this means targeted spraying of weed-prone areas with a mixture of hot water and a biodegradable foam made from plant oils and sugars.

“It’s really simple to use, once you’ve understood the controls on the machine. Basically, it’s like programming a car radio,” says Mr. Greatrex, who is parks and open spaces officer for Vale of Glamorgan Council.

“Although it’s not the magic bullet to replace glyphosate, it has cut down massively on our use of it. And it’s made us think more about what we’re doing overall on the environment, so that’s quite an interesting by-product.”

In their efforts to minimise pesticide use, some are refining abandoned weed-killing technologies of the past – such as zapping weeds with electricity.

“The first patents were in the 19th Century: there were trials on the railroad but they never succeeded because the energy was hard to control,” says Karsten Vialon of precision farming supplier AGXtend.

“And chemistry was so cheap, so easy to use and so efficient that all the companies working on alternatives couldn’t succeed.”

But, he says, as weeds have developed resistance to herbicides, and environmental and health concerns have come to the fore, electricity has become a viable alternative once again.

The XPower system, which attaches to a tractor, kills plants in less than a second by pulsing electricity through them to destroy the vascular bundles that transport water and nutrients.

“Electricity has no residues, a low risk of erosion and high efficiency because we can control the whole plant in a systemic way – all of the plant, including the roots,” says Mr. Vialon.

“We can destroy any plant. The only plant we cannot destroy is a tree.”

Meanwhile, a new device created by the University of Melbourne and spun off into a company called Growave is undergoing trials in Victoria.

Just as a domestic microwave warms food, so the microwaves emitted by the Growave system heat up the water molecules within weeds and cause them to vibrate. This ruptures the cell walls, killing the plant.

Meanwhile, microwaves can also heat the soil, killing weed seeds as they lie.

“Early data is demonstrating that using the Growave technology will be as cost-effective and potentially less expensive than current approaches to weed management,” says Paul Barrett, head of physical sciences of investment firm IP Group.

“The Growave approach also has the benefit that it is not influenced by the elements and can be used when it rains, when it’s windy or even at night – conditions which are not possible with traditional herbicide-spraying approaches.”

And even before anybody gets anywhere near a patch of weeds, technology can be working to minimise herbicide use.

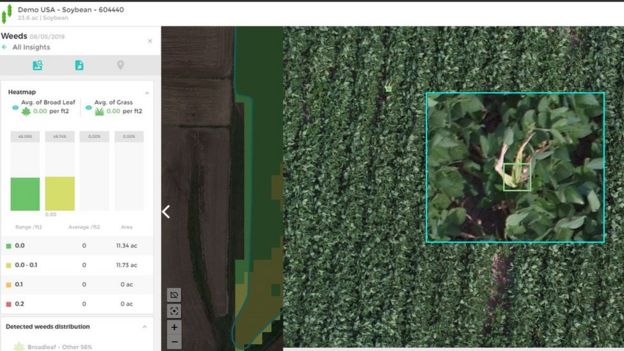

Israeli company Taranis, for example, uses computer vision, satellite and drone imagery to identify precisely what weeds are growing and where, allowing weedkiller to be far more tightly targeted.

“What usually happens with scouting on farms is that scouters will head out to the field and look through different sampling areas of the fields to see if there’s any indication of disease or pests or weeds,” explains the director of marketing Tali Brousard-Shimer.

“We offer scouting with drones and planes that fly over the fields at 200km/h taking pictures of each acre to indicate where there’s any crop stress. These super-high-resolution images – sub-millimetre images – are fed into our platform to identify the actual issues taking place in those areas.”

While human scouts can cover 10 locations in six hours, she says, the Taranis system can manage 100 in six minutes, identifying specific weeds as soon as they emerge. And, once artificial intelligence has done its stuff, the system comes up with a specific prescription.

“If a farmer’s field was sprayed with herbicide pre-planting, and after the planting, there’s still resistant weeds in one area, you don’t want to spray the entire field because you’re creating additional damage,” says Ms. Brousard-Shimer.

With mounting concern about glyphosate – and with few other chemical alternatives – Leo de Montaignac, chief executive of Weedingtech, believes that the alternative market is set to boom.

“I think that we’re only just seeing the very start of this market, and I think that over the next couple of decades, we’re going to see outright bans on traditional chemical herbicides in public spaces,” he says. “This market’s going to explode.”

Source: BBC News