In the first of a series of environmentally-focused landscape articles, environmental consultant, Féidhlim Harty explores how edible species can be incorporated into designed landscapes. As the coordinator of Garden of Eden Projects Ireland, he has a particular emphasis on community projects, but the same plants, pointers and principles can be applied to any garden or landscape design |

We have the potential to add edibles throughout our parks, housing estates and wider landscapes. Hedges can be grown from Corylus, Rubus and Ribes cultivars as well as the more familiar edibles such as Crataegus, Sambuchus and Malus sylvestris. Tall feature trees can include Castanea sativa, Juglans regia or Pyrus sp. Boundaries can be interplanted with any of these trees or with others such as Prunus domestica insititia Malus domestica and even Castanea sativa.

For more formal areas of parks or for domestic gardens, the herbaceous border can be just that – herbs; full of colour, scents and interest for wildlife as well as providing culinary herbs for the kitchen. A range of vegetables can be grown as perennials, providing a yield year after year from the same plant. It’s not a large step from ornamental Brassica varieties to those that also provide a yield for foragers or community groups.

If you want to really cram in the goodness, then a permaculture forest garden can offer an abundance of interest for people and wildlife. These are productive gardens in which fruit trees, fruit bushes, soft fruit, perennial vegetables, edible flowers and herbs are grown together in a purpose-designed mini woodland. Even on a tiny scale of two apple trees and an understory of bushes and herbs, they are ideal for most urban and suburban gardens and can be designed to provide fresh fruit and vegetables almost year-round. On a larger scale, you can have a whole community woodland park composed of a full suite of edibles.

Where low maintenance is a priority, as it will be on many public projects, the designs can be tailored to include more of the larger fruit and nut trees, or fruit bushes, and fewer perennial vegetables and more delicate herbs.

There are lots of reasons to design edible landscapes and gardens for your clients. As well as providing fresh fruit and vegetables, once in place the work and cost can be much lower than growing annuals. Obviously, the more work put in, the more produce got out – yet the beauty of an edible landscape is that even if you sit back and add nothing else, the fruit and nuts still grow on the trees and bushes.

Edible landscapes are very wildlife-friendly. They attract an abundance of birds, butterflies and bees to the varied mix of species present. They’re also great fun for children. There is great satisfaction in picking your own food, whether from your own garden or from local community orchards. With careful design and selection of plants used, the fruit and nut trees and fruit bushes can provide an extended play area which provides healthy, chemical-free food nearly all year round.

In the context of the climate and biodiversity emergency, careful landscape design can actively sequester atmospheric carbon in the soil (capturing CO2 from the air as it does so) as well as providing abundant opportunities for supporting local wildlife. As we see the growing evidence of plastic in our oceans, many of us are moving towards zero waste. Food from the garden doesn’t come in plastic!

WHAT PLANTS CAN BE USED?

The variety and number of plants that you select will be dictated by the conditions on-site; such as site size, topography, existing planting layout and soil characteristics: depth, drainage, and chemistry. Malus and Pyrus sp., for example, won’t appreciate damp heavy soils or a high water table. For challenging sites you may want to include nurse crops like Alnus, Symphytum, and Lupinus sp. to break up the soil a bit or to fix nitrogen. As the edibles begin to grow and take their space, the Alnus can be taken out and will leave a supply of nutrients and biomass in the soil to support the developing fruit and nut trees.

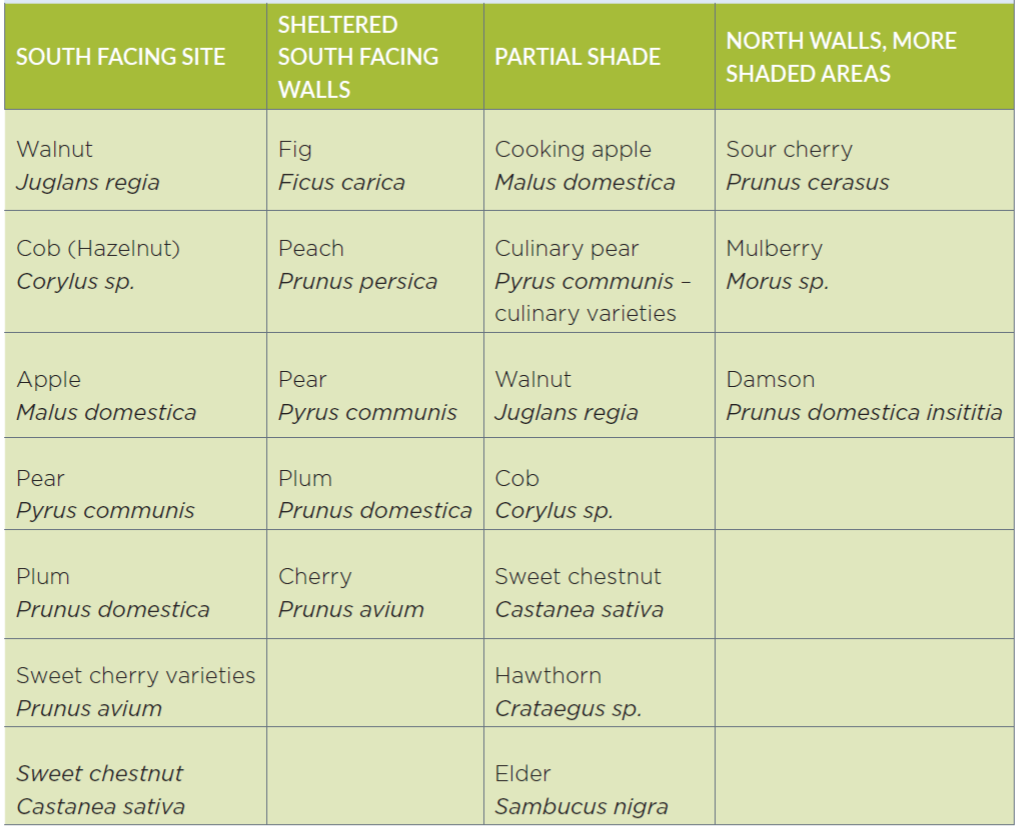

| Most trees prefer relatively good sunshine, but some will tolerate shade more than others. Here are some examples of suitable trees for edible landscaping in different shade conditions: |

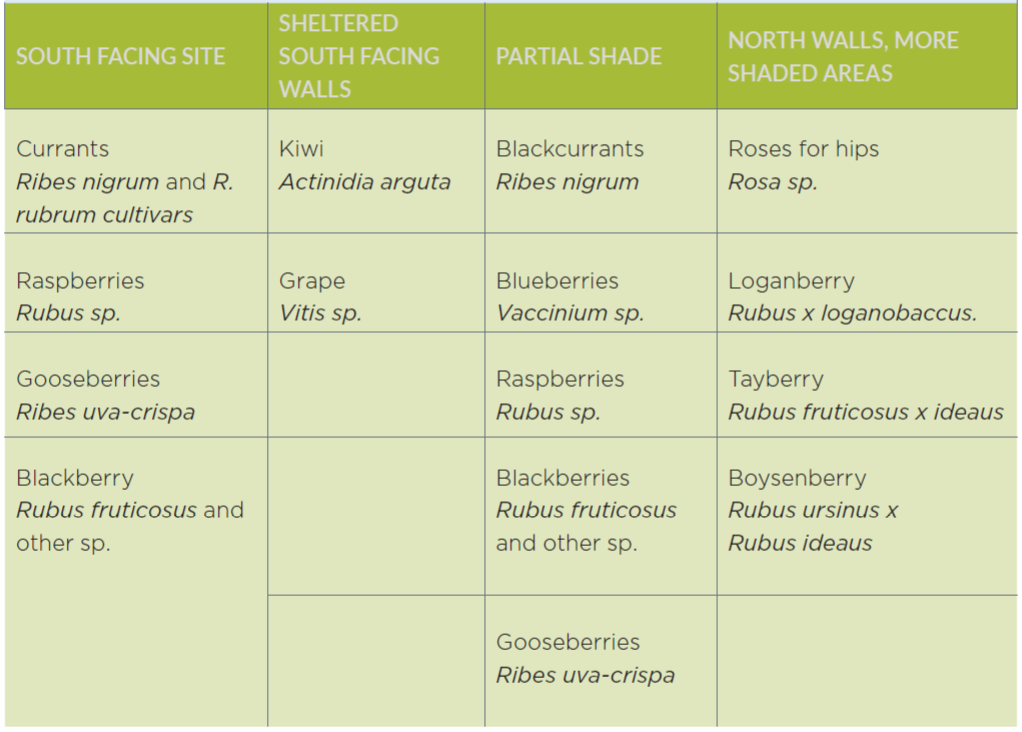

| The same is true for bushes and climbing fruit. Examples of suitable shrubs and climbers: |

Typically, edible landscape designs will include fruit trees, nut trees, fruit bushes and cane or climbing fruit, perennial vegetables and edible flowers – or a selection of some of these categories depending on the design. If you’re designing a park, for example, you may include more trees, bushes or flowers and fewer vegetables. A simple orchard layout can work well for community projects in public space. You can plant 6 trees in an hour or two, or 60 in a day if you have a group of volunteers on hand to dig holes, barrow compost, and stake new whips.

“With careful design and selection of plants used, the fruit and nut trees and fruit bushes can provide an extended play area which provides healthy, chemical-free food nearly all year round”

When it comes to edible ground cover plants, most culinary herbs are Mediterranean in origin and will thrive in full sun or partial shade. Foeniculum vulgare, Myrrhis odorata and Mentha sp. are particularly good in fresh teas as well as cooking, and very easy for gardeners or visitors to the park or community space to identify and use. Many herbs are also happy with a bit more shade, such as Thymus sp., Petroselinum crispum, Mentha sp., Matricaria chamomilla, Anethum graveolens, Salvia officinalis, and Allium schoenoprasum.

Perennial vegetables such as Brassica oleracea var. Ramosa and Brassica Oleracea Botrytis Asparagoides can be used in full sun or partial shade and produce quite happily for much of the year. Vegetables such as Valerianella locusta, Beta vulgaris, Brassica oleracea and B napus varieties self-seed easily, so they will come back year after year if the conditions for germination are good. Make friends with native edibles such as Rumex acetosa and Teraxacum officinale, since these produce vegetables for the pot or for salads even amid competition from grass. In conventional gardening terms, these are called weeds – but if you start to eat them it shifts the focus somewhat.

LAYOUT AND MAINTENANCEOften the richest most abundant growth takes place at the interface between different habitats. In permaculture design, there is an emphasis on using and valuing the edge. Thus, in forest garden design, the woodland edge is the one that is encouraged. To allow for this, apple and pear trees may be planted that bit further apart than in standard orchard layout, allowing for edge habitat of bushes, climbers, herbs, flowers and veg interspaced throughout the planted area. Naturally, any design will be steered to some extent by the starting layout and conditions of the site. If you find yourself with a large sheltered south-facing wall, then go wild with Ficus sp. and Prunus persica and find a less benevolent spot for the hardier Malus and Juglans sp.. You’ll have a greater selection of suitable trees if you have a good rich south-facing slope and will be more limited on a cold site with heavy soil. But there will always be options available. To remain at their most productive, fruit and nut trees need a supply of nutrients to keep them happy for many years. If you follow standard apple tree planting advice and add a generous bucket of compost in the base of the planting hole, that will get the new trees off to a good start. But it won’t last indefinitely. An occasional top dressing of compost or well-rotted manure works wonders if you can manage it, but on community projects such as parks and public spaces, the budget and workforce for regular maintenance may be more limited. Although convenient, artificial fertilisers have distinct drawbacks in that they reduce the effectiveness and numbers of healthy soil microorganisms. It is these communities of fungi, bacteria, worms and other life within the soil that keep it vital, vibrant and alive, so they are to be supported as much as possible. In the past, I’ve used mycorrhiza fungal mixes and microbial preparations to help seed poor soils with the right microflora and fauna to nurture the trees into the long term. Companion planting is another way to help plant communities of plants that will support one another with relatively little input after the design and planting date. One of the ways I have found to provide nutrients in the longer term is to use aged woodchips as a surface mulch around the trees. This will reduce the available nitrogen in the early years, but as it breaks down it will provide nourishment for the developing roots. Often woodchips are available in abundance from local tree surgeons, so you can get the benefits of weed suppression, aesthetics and longterm soil enhancement for free. CONSIDERATIONS FOR PLANTING IN PUBLIC SPACESThere are several preconceptions that people tend to have about creating productive beautiful edible landscapes in public spaces. The words rat, littering, vandalism and anti-social behaviour are sometimes heard at the beginning of a community planting project. Certainly, many different species of wildlife will be attracted to fruit and nuts if they lie on the ground but bear in mind that rats are already well catered for by human’s propensity for untidiness and a few more fruit trees will be much more likely to attract blackbirds, finches and tits than rats and mice. Similarly littering is a common problem even without the fringe benefits of fresh fruit and nuts. In relation to vandalism and anti-social behaviour – the severity will depend on where the project is located, how much local buy-in there is during the planning, planting and maintenance, and/or how much people even know that the project exists. One measure I have taken on some of the projects I’ve organised locally is to simply avoid advertising it too widely. Without extensive local coverage in local papers or radio, a new orchard can pop up in a green space without even being noticed. This may not make for great marketing but has the distinct advantage that the new trees get a good head-start without undue negative attention. After a few years, the trees will be well established, and we can advertise community events such as pruning workshops or foraging days to our hearts’ content. Another measure I’ve adopted is to plant lots of small trees. The budget is similar to a small handful of tall standard trees, but the former is much easier to plant as part of a community event. If these are interplanted with cuttings of Salix alba and S. viminalis then the number of small trees can grow exponentially at no extra cost, making the expensive fruit and nut trees much less of a target for theft or harm. The Salix can then come out after a few years by coppicing heavily in August for a year or two. Certainly, if we create a beautiful space that people want to visit and socialise in, surely, we’ve done a good job. Sometimes that will include drinking, but in my experience, the fear of antisocial behaviour is mostly overestimated. By contrast, the threat of the current climate and biodiversity emergency is dramatically underappreciated. If given the option to leave a quiet corner to grass, or make it into an area of beauty, sociability, recharge, carbon sequestration, food security and biodiversity – I’ll steer toward the edible landscape option every time. ✽ |

FÉIDHLIM HARTY is the director of FH Wetland Systems environmental consultancy and writer. His most recent book is Permaculture Guide to Reed Beds. FÉIDHLIM HARTY is the director of FH Wetland Systems environmental consultancy and writer. His most recent book is Permaculture Guide to Reed Beds.For more information on his publications and service visit wetlandsystems.ie |