Aidan J ffrench MILI disseminates a recent research conference paper on the drivers, reality and potential future for green infrastructure in Ireland

February 2007 IUF publishes its General Election manifesto – ‘A Better Quality of Life for All’ – containing proposals for sustainable planning, site tax, green infrastructure (landscapes, parks), housing and transport. The manifesto gained extensive media coverage and was well received by political parties. Simultaneously, ILI published ‘A Manifesto for Irish Landscapes’, which was only partly incorporated in the 2007 Programme for Government. October 2009 – the Irish Urban Forum (IUF) revised manifesto examines the economic boom’s hangover effects, pointing to oil and car dependency, urban sprawl, infrastructure and housing demands.

The seeds of economic crisis and austerity – sown during Ireland’s flirtation with the resource-hungry, economic neo-liberalism – grew alongside planning corruption and ineptitude. The results impact deeply on citizens, severely diminishing their quality of life, and marginalising environmental imperatives.

2016 – Ireland faces critical challenges: unrestrained urbanisation, car dependency, declining health, aging population and political inertia around Blue-Green Infrastructure (B-GI). Climate change is real and present. Severe flooding threatens lives. A fragile economic recovery is set against a background of impoverished public services. There’s a housing crisis, there are inequitable health services and infrastructure deficits – all driven by ongoing neo-liberalism and dysfunctional governance.

Despite this, inspiring examples of progress exist, driven by civil society and state actors. Community activism in placemaking, urban horticulture and ‘green exercise’ has emerged, with the potential to advance B-GI with socioeconomic benefits.

LESSONS AND IMPERATIVES

The IUF/ILI manifestos remain conspicuously relevant. But, a facile mantra – “the lessons have been learned” – has emerged, vague and unsubstantiated: evidence of significant

deficits prevails. The longstanding failure to put parks and landscape services (P&LS) on a statutory basis is inexcusable: still an optional function for councils (solely in the gift of

senior management, dependent on patronage/bureaucratic whim; with mandarins and management ‘captured’ by the seductions of ICT and ill-conceived ‘reforms’. Very few of

the 31 councils provide P&LS or employ landscape architects horticulturists, tree or biodiversity officers. Ireland is an embarrassing laggard, compared to more progressive

countries. For 16 years ILI has called on successive governments to take action.

Few lessons have been learned. Mindsets and values remain unaltered, subservient to flawed ideologies and rhetoric. A client list culture is disengaged from urgent environmental

issues, with pressure on politicians, addicted to short-term thinking. For many, resumption of ‘normal service’ (Celtic Tiger style), would be welcome.

The Irish, not known for their environmental consciousness (a minority sport?), seem wedded to the dominant capitalist ethos of unfettered materialistic, consumptive lifestyles,

of which Pope Francis so eloquently warns us in his inspiring eco-encyclical, Laudato si.

Significant deficits in policy, law and investments are self-imposed errors, revealing Ireland’s comparative delinquency, vis-a-vis progressive states and cities (Sweden, Germany, Netherlands, Portland, New York, Vancouver). The general election in 2016 reflected this malaise. The minority government eschews a radical shift towards genuine sustainability, ignoring vital capital investment in infrastructure, sustainable communities,

GI and services. Severe reductions in resources (e.g.28% – 10,600 less staff in councils) are constraining the public sector’s capacity, harming Ireland’s competitiveness and sustainability.

Urgent imperatives include:

● COP 21 Paris – targets to reduce CO2

● Climate change adaptation – sectoral plans a legal obligation (Climate Action & Low-carbon Act, 2015)

● Housing/sustainable communities and public health

● B-GI – outdated Parks Policy (1987) requires modernisation, statutory obligation and investment.

DEFINITION

Any definition of B-GI should reflect the varying emphases of planners, ecologists and landscape architects. GI is inherently cross-disciplinary and ‘silo-busting’ (e.g. conventional ‘grey’ infrastructure meets eco-landscape design).

The following is proposed: –

● The planning, design and management of natural, semi-natural and manmade environmental assets and resources, for socio-economic-ecological goals, by studying,

understanding and applying their inherent multi-functionality and ecosystem services, through policy and practice.

Warning! The definition is anthropocentric – critics of GI’s natural capital approach point to naive expectations and questionable ethics. Nature’s intrinsic value is independent of Homo sapiens. Pope Francis has eloquently expressed the dangers of econometric-technological reliance. So, will the Anthropocene usher in enlightened self-interest?

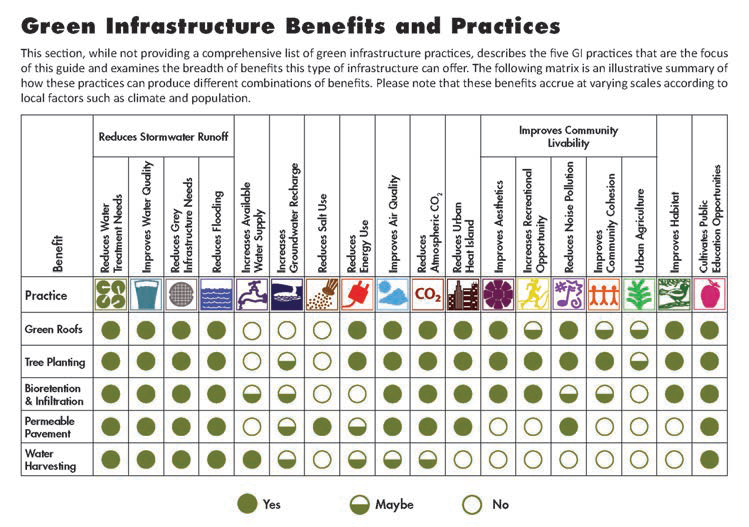

Fig. 1. GI practices and benefits

PROJECTS AND INITIATIVES

A B-GI placemaking approach can evoke earth stewardship. Linking GI and placemaking is a happy synergy: many projects bear testimony. Some involve admirable volunteerism,

evocative of previous generations’ love of the meitheal (seasonal gatherings in rural communities, with collective harvesting). Meitheal – an act of mutual, neighbourly support – is related to placemaking. Meitheal partly fulfils humans’ innate desire for belonging to a place, expressed by the late John O’Donohue, that most loved of poet-philosophers and lover of Irish landscapes. Meitheal is not confined to rural life; it’s alive in urban communities and horticulture projects. A model worth expanding.

EXAMPLES

Irish GI is relatively new and varied as shown by some randomly selected projects, with shared characteristics, such as visioning, partnering and collaboration.

National and Regional levels

● The Wild Atlantic Way and Mayo Greenway: Fáilte Ireland and Mayo Co Co. 2,500 km long, with places designated as points of interest; objectives include local economy stimuli, sustainable eco-tourism

● Heritage Council Grant Scheme: HC’s admirable expertise, successes in fostering, promoting partnerships and community projects is a testimony to vision, the persistence of a state agency that’s survived recessionary cutbacks providing inspiring public service.

Local level – Dublin

● Dublin Bay UNE SCO Biosphere special UN designation, intimate to Dublin city. Biosphere Partnership (DCC, DLRCC, FCC councils, Department of Arts, Heritage, and the Gaeltacht, Dublin Port) runs the project

● Temporary urban landscapes (arts, community gardens etc)

● Dublin: various project from the early 2010s, in the inner city, on abandoned, derelict sites, led by grassroots community activist

● Dublin Mountains Partnership (DMP)]: active recreation in peri-urban landscapes (SW County Dublin); partnership – 3 councils (Dlr, DLRCC, SDCC, DCC), Coillte, Dublin Mountains Initiative, NPWS, with landowners

● Shanganagh Community Gardens, Shankill, active citizenship/community gain, from ‘grey’ infrastructure project (sewage plant); a committee of local growers, located in a low-income neighbourhood; social engagement a strong key to success

● Community Placemaking URBACT EU Project: DLRCC Community-led (Enterprise Officer); capacity-building, social capital in disadvantaged housing estates in Loughlinstown; results = stronger sense of place identity, empowerment of previous disengaged residents, enhanced environment

● DLRCC Green Infrastructure Strategy 2016-2022. A multidisciplinary project, jointly delivered by Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown’s P&LS and planning departments with a team of consultants, that is integral to DLRCC’s new County Development Plan 2016-2022, giving it a legal status. It will contribute to DLRCC’s climate change strategy.

DLRCC’s GI has contributed significantly to the county’s reputation as a vibrant place with a high quality of life and vital to the socio-economic and environmental wellbeing of the county. The strategy has three mutually reinforcing themes:

1. Accessibility, recreation, health and wellbeing: quality and continuity of GI connections (greenways, walking routes); access to open spaces and recreational resources; activities

in key amenities

2. Natural heritage: natural and man-made assets of value; areas for biodiversity (watercourses, woodlands, coastline)

3. Water management: opportunities for CC adaptation, GI to optimise stormwater management and water quality.

Spatial Framework

A structure for decision making and interventions, it spans short to long term, identifying existing and planned GI:

● Six multi-functional corridors connecting higher level hubs, mountains, urban areas, coasts

● A chain of improved gateway hubs (parks), in transition between the mountains and the urban areas

The framework reflects DLRCC’s slogan – “O Chuain go Sliabh” – as the county is located between Dublin Bay and Dublin Mountains.

DELIVERY

A robust approach is essential, pointing to an opportunity for DLRCC to build new partnerships; key recommendations:

● A multi-disciplinary, inter-departmental working group reporting to CE

● Delivery plan

● Local and external funding

● Tools for integrating GI into planning

Fig. 2: DLRCC Strategy: Spatial framework

PILOT PROJECTS

The strategy harnesses existing initiatives while recommending specific pilot projects to demonstrate benefits. Projects include constructed wetlands, green streets, and sustainable urban drainage schemes. Green streets could help DLRCC meet its obligations under the EU Water Framework Directive, attenuate flooding; contributing to placemaking by enhancing aesthetics, biodiversity and public participation. Criteria is being drafted now for selecting

streets for retrofitting as green streets, based on best international practices.

CONCLUSIONS

“The measure of any great civilization is its cities and a measure of a city’s greatness is to be found in the quality of its public spaces, its parks, and squares.” – John Ruskin

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH AND SUSTAINABILITY

Volunteer ethics and practice remain strong, aided by dedicated public sector champions. In future, civil-society – public sector alliances could radicalise public consciousness,

bringing concerted pressure on the political system to fully address deficits.

Key lessons

● Build healthy, synergistic relationships between Civil Society and State (e.g. leverage Tidy Towns Movement to boost local horticulture entrepreneurship through local enterprise offices)

● Don’t rely on a narrow relationship model (OECD 2006: Ireland’s relations-based society is prone to cronyism, corruption, unlike systems-based societies, e.g. Germany)

● Prioritise systemic governance (policy, law), invest in services and people

● Put GI and landscape services on a statutory basis (as a core service with drainage, housing, information and communication technologies, roads, planning. As long as it’s optional, delivery will remain weak

● Dissembling some myths regarding urban parks –

- They are not luxuries – they’re vital to human well-being, economy and resilience

- They are dynamic assets – vital to culture, economy, tourism, leisure, social cohesion, prosperity, biodiversity

- They are indispensable to climate change adaptation

These claims are based on a growing catalogue of evidence-based research by academics, think tanks and agencies. Views expressed are the authors and not those of the ILI or DLRCC. A copy of the full paper and list of references is available from the author on request. ✽

Aidan J ffrench MILI is a registered landscape architect, chair of the Irish Landscape Institute (ILI) working group on green infrastructure, former ILI President (2005-2007), and is a member of European Foundation for Landscape Architecture’s Landscape Policy Group. He can be contacted via email at affrench@dlrcoco.ie Aidan J ffrench MILI is a registered landscape architect, chair of the Irish Landscape Institute (ILI) working group on green infrastructure, former ILI President (2005-2007), and is a member of European Foundation for Landscape Architecture’s Landscape Policy Group. He can be contacted via email at affrench@dlrcoco.ie |