Imagine if the solutions to climate breakdown were staring us in the face all this time – we just hadn’t yet seen them. Instead of being bamboozled by ever more depressing news reports, imagine if the answers to our manifold problems were self-evident and beautifully practical. If it wasn’t an either/or situation, where we had to choose between climate or biodiversity or earning an income or having a thriving society. Imagine for a moment where any choice we made in one arena supported the health and wellbeing of every other aspect of our lives.

Let’s take a look at how this imagined scenario might have a solid foundation in reality.

Something clearly isn’t working with our current responses to climate breakdown. Despite the calls for change on so many levels, the focus of international government, business, academia and media are firmly hooked into economic growth as the only societal model of choice. We seem to be averse to setting limits, even as we watch in dismay, shock, denial or horror as the world’s life support systems fall into ruin around us.

The problems all seem too large to address on a local level, so we brainstorm and organise, trying to reach the ears of government and UN Climate Change Conference (COP) negotiations, where we feel that the real decisions are being made. Carbon is the predominant focus, but perhaps there is more to this issue than just carbon. Let’s take our attention off the carbon model for a sec and explore other routes forward.

Take note: there are many excellent reasons to unhinge our society from economic growth as our main social model and the over-reliance on fossil energy that goes with it. However, for local practical solutions, restoring water dynamics and habitats may be a better fit.

WHAT IS CLIMATE BREAKDOWN?

First let’s look at what we mean by climate breakdown. Generally the images that come to mind are flooding, droughts, wildfires, sea level rise, biodiversity loss and the like. Well, while the COP negotiations are doing their thing, I propose that we can address all these and more in a much more effective way than canvassing politicians on our doorsteps or signing petitions (all of which have their use too, by the way).

START WITH ONE FARM POND

There is something I’ve observed in my work with land and water management over the years. It may not sound very exciting, or even terribly novel, but it’s relevant to this discussion. If I build a wildlife pond in a farm drain, I notice that a number of things happen.

Firstly the water flowing out will generally be cleaner than the water flowing in. That’s because the large volume in the pond slows down the speed of the water compared to the flow rates in the drain feeding it. Silt – which was carried along by the faster flowing water – begins to settle out onto the base of the pond. Nutrients are also captured by algae and growing plants, helping to clean up the water further.

When it rains, the pond tends to hold more water than the fields that it replaced, with their field drains all speeding the movement of water from the land and into the drain. Thus the new pond acts as a sponge within the landscape. Heavy rain gets stored and then slowly released after the shower passes.

So what have we just done? By simply creating a pond in a drain, we have helped to balance the water flow dynamics in one easy process. As far as the small open drain is concerned, humans have just sorted out climate change, pure and simple. The drain notices a tangible reduction in both flooding and droughts, the two key symptoms of climate breakdown on a local catchment level. We’ve also improved water quality and replaced lost habitat – the nuts and bolts of addressing our biodiversity crisis as well. All with that simple wildlife pond in a farm drain.

If we added ponds on all the drains in a local stream catchment, the main waterway would begin to experience the same hydrological regulation; the same reduction in floods and droughts that each drain is noticing. This effect would be all the more pronounced if we added flow control measures, such as in-channel leaky dams or porous outlet pipes at the low end of our ponds, depending on the site requirements.

THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

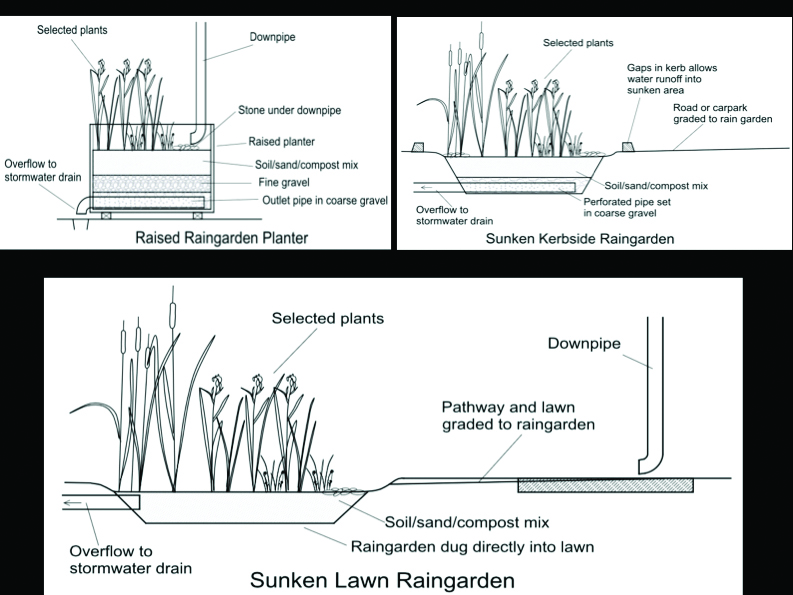

This same mechanism applies with urban SUDS (Sustained Urban Drainage Systems), whereby water exiting paved surfaces is stored and then slowly released. My preferred SUDS systems are usually the planted versions rather than large concrete or plastic tanks. Measures such as green roofs, ponds, wetlands, bioretention areas, swales or rain gardens (shallow, broad, vegetated channels and areas designed to store, filter, infiltrate and/or convey runoff from paved surfaces) all offer biodiversity and filtration benefits, as well as stormwater storage. (See horticultureconnected. ie/horticulture-connected-print/2020/spring-2020/site-drainage-with-an-eco-twist-feidhlim-harty.)

It can be difficult to appreciate the value of rainfall in the Irish context. We seem to suffer from too much rain rather than not enough of it. Consider, however, that our current national water plans include piping part of the River Shannon across from the West of Ireland to Dublin in order to meet demand in the capital. Rain falls on the east of the country as well – we just pipe it into rivers all too quickly. If we were to put water back in the ground where it belongs, whether on farmland or in urban space, we could easily meet Dublin’s growing water requirements locally.

PLANTING RAIN

The process of reinvigorating the water table is sometimes called ‘planting rain’. It is part of an often overlooked element within the water cycle. What we learned at school was only ever half of the water cycle: moisture evaporates from the sea and moves inland as clouds, where it falls as rain, enters streams and rivers, and flows back to the sea again. That is the visible half, all above ground.

A crucial element of the full water cycle is where rainfall lands on the soil and soaks into the ground beneath, recharging the water table. This groundwater emerges as springs within the landscape when it is good and ready, and flows from there to streams and rivers. Without this important step, we are ignoring a vital part of the whole picture – and a lot of potential stored water.

The benefits of stored water are much easier to see in arid climates, where the impacts of conventional water management and revised management contrast much more acutely than here at home. In conventional water management, we tend to get rid of urban or agricultural runoff as quickly as possible, leading to the inevitable flood/ drought scenarios that we see on the news so regularly. By contrast, if we plant rain via ponds, swales and bioretention areas, we can recharge water tables, get springs to flow again and literally re-green deserts.

John D Liu has written and spoken at length of the amazing work in the Loess Plateau in China, where land management practices designed to hold water have shifted the fortunes of both wildlife and people within this once arid landscape. Similar stories come to us from Geoff Lawton’s permaculture work in Jordan, the experiences in Tamera in Portugal, Rajendra Singh’s water work in India, and from many other places around the world. In each case we see example after example where direct, practical changes in land use and water management have taken effect over remarkably brief timeframes, recharging water tables and reducing or reversing the local impacts of climate breakdown.

NOT JUST PONDS

Of course, it’s not just ponds and SUDS. Wherever an opportunity exists to slow the flow and allow rainfall to soak into the soil, water can work its magic. In Ireland, the largest land use type is our farmland. That’s a lot of land receiving rainfall during every cloudburst. Good humus-rich soils are high in carbon, which not only locks up atmospheric CO2, but also provides the soil structure to hold water. Humus can hold up to 20 times its weight in water. The challenge with our soil, however, is that for the past 50 years or so we’ve been using artificial nitrogen fertilisers, which actively denude soil carbon. Without carbon, the soil loses its capacity to hold water. That precipitates a vicious cycle of rapid water runoff, accelerated soil erosion, nutrient losses and the inevitable water pollution and flood/drought cycles that ensue. Less soil and nutrients, means poorer crop growth; leading to more nitrogen fertiliser additions.

However, we can spin it the other way into a virtuous cycle, by adopting the techniques of regenerative agriculture instead of chemical based farming. This approach builds soil carbon, increasing both water holding capacity and drainage, improving the availability of nutrients for plants, reducing water pollution and regulating catchment hydrodynamics. Indeed, in Ireland we’re seeing an encouraging move to adopt regenerative techniques, which include cover cropping, multi-species swards agroforestry, silvopasture and the like.

TREES AND THE BIOTIC PUMP

Both agroforestry and silvopasture (the integration of trees into the farming landscape as a crop and/or shelter belt or pollinator haven in their own right) also provide benefits for water. We all know that trees take up a lot of water and evaporate it from their leaves. It’s less well known that trees release microbes and organic compounds that act as condensation nuclei to make rain again. Not only that, but a team of Russian physicists are finding that forests also generate wind, which encourages moist air to be pulled inland to help keep up the high moisture content that trees love. In this way, forests act as biotic pumps, pulling moist air in from the sea and cycling it from tree to tree ever further inland.

The drying of the Amazon basin is a tragedy of global scale, and can easily be attributed to climate breakdown. However, a further and often overlooked factor is staring us in the face: namely, if we remove the forest cover along the coast of South America, we’ve broken the biotic pump. No amount of carbon negotiations will fix that pump. What we need to do is fix the pump by reinstating natural forest cover again. We can do that by exploring why the forest was cleared in the first instance: for example, among other things, to grow soy meal for export to Ireland’s many cattle (who already have the best grass in the world); and then by paying Brazilian farmers marginally more to reinstate forest cover than to create cropland.

WILDFIRES, SEA LEVEL RISE AND BIODIVERSITY LOSS

Let’s close on some of the remaining symptoms of climate breakdown and see whether water has a bearing on any of them. Wildfires apparently owe much of their origins to the steady depletion of water tables for agricultural irrigation. Once the tree roots can no longer reach the groundwater, a tinder dry upper canopy begins to make wildfires in California or the Mediterranean basin look inevitable.

In terms of sea level rise, certainly glacial melt has a huge bearing, but consider other land-based liquid water as well; groundwater and surface water. NASA research has shown that the intensity of storms in the southern hemisphere during 2010/11 were such that rainfall in South America, Australia and South-east Asia lowered global sea levels by a full centimetre – such was the volume of rainfall moved from the sea to the land. That’s without reference to actively managing our landscapes to hold water. If we were to recharge groundwater, introduce habitat, include woodlands and trees within our farming models and plan for water rather than planning to get rid of it as quickly as possible, just think of the benefits for sea levels.

Biodiversity loss and habitat destruction are often seen as symptoms of climate breakdown. But what if they were among its primary causes? What if we took all the fear, grief and love that we feel for the world and, instead of trying to get politicians to change from business as usual, we used that energy to create habitats in our own farms, gardens and catchments? What beauty could unfold?

Habitats within the soil itself; within our waterways; within diverse woodlands and riparian corridors. Habitats within hedgerows and steeply sloping fields or awkward corners. Habitats at a remove from food growing completely in rewilded areas; wild river corridors and wild regenerating uplands. The beautiful diversity of all of life, from the microscopic to the largest of species, all supported and encouraged to thrive.

One thing is certain. Wildlife would thank us, water would thank us, and the beleaguered climatic systems which regulate our own comfort on this blue bauble of an oasis would thank us. ✽

FÉIDHLIM HARTY is an environmental consultant, writer and educator, focusing on land management solutions for improving water quality and hydrodynamics; recreating habitats and revitalising biodiversity; and providing local, practical solutions to the climate and ecological crises – one stream catchment at a time. For upcoming workshops visit www.wetlandsystems.ie.