A few posts have popped into my Facebook timeline recently asking questions about the Harlequin Ladybird (H. axyridis), or sharing dramatic headlines from tabloid newspapers:

“how to spot a sex crazed invader”

or

“biting alien ladybirds riddled with STDs are swarming the UK in their millions posing a threat to our native bug”.

During a return to college earlier this year, my chosen invasive species for an Ecology assignment was this colourful little beetle. Now seems a good time to share some of my findings. In the following article, we’ll look at why invasive species, in general, are a problem, how to identify the Harlequin Ladybird, how quickly it breeds and spreads, its preferred habitats, what to do if you experience an autumn invasion, and finally how to report a sighting.

But first, how worried should we be about invasive alien species?

photo credit: MacRo_b Harlequin Ladybird #2 via photopin (license)

Why is the Harlequin Ladybird a Problem?

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reports that “invasive alien species, of which Harlequin Ladybird are one, are the second most significant threat to biodiversity after habitat loss, capable of causing significant damage to human health and the economy”. The costs are considerable; controlling and repairing the harm invasive species do in the EU alone, amounts to over €12 billion per annum.

Research has shown that Harlequin Ladybirds contribute to a reduction in biodiversity by directly competing with other invertebrates for food and habitats. In the absence of aphids and scale insects, Harlequins predate on the eggs of native ladybirds, as well as moths, aphids, eggs and larvae of butterflies and other scale insects. In 2005, a UK Ladybird citizen science survey recorded that seven out of eight assessed native ladybird species were in decline due to the Harlequin Ladybird. Additionally, it has been shown to host several parasites, one of which has been linked to the decline in native ladybird species.

How did the Harlequin Ladybird get here?

The Harlequin Ladybird is already established on the island of Ireland and it’s unlikely that it can be further prevented from entering, though the Irish sea has been a limiting factor in keeping it from our shores. Fresh vegetables, cereals and cut flowers have been its main pathways in.

Introduced widely across the USA, Canada, and continental Europe, as a means of controlling pests biologically in glass houses, primarily aphids and scale insects, the Harlequin originated in Asia. From 1995 it was sold by various biological control companies in the Netherlands, France and Belgium and was intentionally released in at least nine other countries. This, combined with its ability to easily escape from glass houses, resulted in the establishment of the invasive species across Europe, North America and Canada.

From 2002, the spread had begun and the Harlequin Ladybird’s ability to adapt to new habitats gave great cause for worry, resulting in it being placed on the European Commission list of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern. Due to its spread in Europe, and more recently in Northern Ireland, the National Biodiversity Centre listed the Harlequin Ladybird as a ‘most unwanted potential invader’ in the Invasive Species Ireland 2007 risk assessment. It was finally noted as Established in the Republic of Ireland in 2010 after two breeding pairs were identified in Cork City in 2010, and in 2011 in Co Carlow. Since then its geographical spread has increased.

“An estimated congregation of 20,000 were recorded in one site in the US.”

Does the Harlequin Ladybird bite?

The Harlequin Ladybird can be a nuisance to humans as they congregate in houses during the autumn months searching for overwintering sites, often in their thousands. An estimated congregation of 20,000 were recorded in one site in the US. Reports have been made about staining of soft furnishings and an odd smell from the secretion of reflux blood that can exude from Harlequin Ladybird leg joints if under attack. A small number of allergic reactions have been reported in the UK as well as bites, but they are rare.

photo credit: Hornbeam Arts Hibernating harlequins via photopin (license)

“Harlequin Ladybirds can have an impact on the quality of wine. This is mostly because the invertebrate are difficult to separate from the grape harvest.”

What does the Harlequin Ladybird Eat?

Apart from other insects and their larvae mentioned above, Harlequin Ladybirds feed on grapes, pears, and raspberries at the end of the growing season which doesn’t significantly impact yield but the quality of fruit can be affected.

Studies in Switzerland in 2009 showed that if there’s a presence of Harlequin Ladybird when grapes are harvested, it has a negative impact on the quality of the wine. This is mostly because the invertebrate is difficult to separate from the grape harvest.

Where does the Harlequin Ladybird live?

Harlequin Ladybirds thrive in a range of habitats and climates. In the UK researchers found that the Harlequin has successfully established in the urban land, as well as in rural locations. In the UK Ladybird Survey, 56% of sightings were in mixed or broadleaf woodland, 29% were within deciduous trees and shrubs such as limes, maples, birches, and roses including stinging nettles, 11% evergreen trees and shrubs, and 4% grasses and others.

How do I Know if it’s a Harlequin Ladybird?

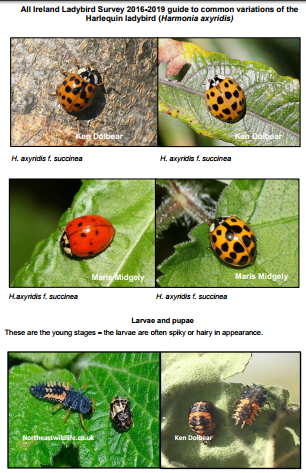

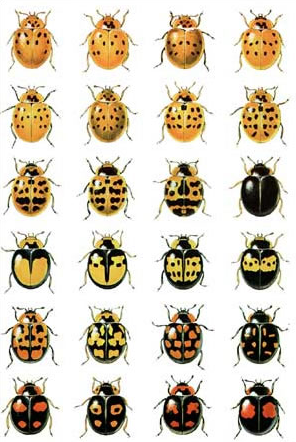

The multicolour variations of the Harlequin Ladybird are the reason for its name. A general description is that it can be yellow to orange to red, the number of spots can range from 0 to 20 and it is between 6-8 mm in length.

Harlequins tend to be larger than most native ladybirds and more domed shape, often with reddish-brown legs. They usually have a distinctive W or M marking on the back of the head. Young Harlequins may have orange stripes on each side of their body. The most common form reported to neighbouring surveys in the UK is orange with 15-21 black spots and black with two or four orange or red spots.

photo credit: bramblejungle Harlequin nymph (Harmonia axyridis) via photopin (license)

The reason for the diverse harlequin effect is that researchers have noted “phenotypic adaptability in relation to colour and pattern polymorphism”, or in other words, their colour and pattern adapts according to their habitat. Three main colour morphs have been reported in the UK with ranges in temperature influencing the polymorph. The larvae that eclosed later in the year had larger spots than those eclosing in spring and early summer and were generally the darker variants. It is thought that this enabled the Harlequin to successfully overwinter, due to being able to blend better into surroundings.

How Quickly Can the Harlequin Ladybird Spread?

It can take up to 25 days for new Harlequins to appear once eggs have been laid from females that have mated in the springtime, longer in cooler areas. Eggs will hatch in three to five days with the larval stage lasting 12 to 14 days and the pupal stage (that happens on leaves), lasting 5 to 6 days. The adults can live two to three years and will survive if they can overwinter in protected sites. Adult Harlequin Ladybirds can reproduce at least two times in a year, up to five times if conditions are favourable, though this is unlikely in Ireland. A full identification sheet can be found below:

photo credit: Marcello Consolo Harmonia axyridis copula via photopin (license)

“The most invasive ladybird on earth and one of the fastest-spreading invaders worldwide.”

How Can We Control the Harlequin Ladybird?

The Harlequin Ladybird has been described as the most invasive ladybird on earth and one of the fastest-spreading invaders worldwide. Methods of control and understanding about the species’ natural enemies are still being researched. Some beetle eating birds such as swifts and swallows successfully predate on other ladybird species, as well as various ant species. Indications are that it is less susceptible to attack from native pests and diseases than other ladybird species. It is thought this will change as natural enemies adapt and evolve. On attack, the Harlequin Ladybird secretes a powerful pheromone as well as toxic reflux blood that deters predators and, along with the red and black colouring that act as a warning, have allowed it to proliferate.

A mite has been identified that makes female Harlequins infertile, but it was found to make other ladybird species infertile too so has been disregarded as a biological control without further assessment.

Harlequin Ladybirds originated in warmer environments and it has been found that cold temperatures prevent it straying to colder countries.

photo credit: bramblejungle Harlequin ladybird (Harmonia axyridis) via photopin (license)

Report it. Become a Citizen Scientist

If you’ve got this far and you think you’ve identified the Harlequin Ladybird accurately, take a photo of it, top and underside, preferably next to a coin or ruler for scale, and submit a sighting. You can either submit to the National Biodiversity Data Centre or to the Ladybirds of Ireland Survey. The more sightings we can submit, the greater the understanding of researchers.

Keep an eye out in imported plants, vegetables or food sources for the Harlequin, don’t import it, report it.

Will My Home be Inundated?

Fortunately, we don’t have the kind of numbers mentioned in the US just yet, though it is a good idea to keep a look out during the autumn months to see if clusters are beginning to appear and look for overwintering shelters.

Should you spot a congregation, after recording it the most immediate and cost-effective method for eradicating the species that I came across during my research was vacuuming, both indoors and out. In households, a regular vacuum cleaner can be used and out in the field, by use of back-pack insect packs or leaf vacuums.

If you’d like to learn more about the information I unearthed during my research, or more detailed references for published papers, please contact me.

Have you come across the Harlequin Ladybird yet? Did you report it?