| John Murphy reflects on the implications, concerns and also the opportunities for plant health in Ireland

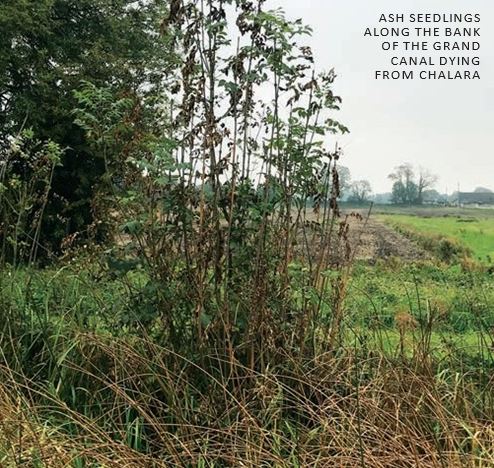

The year 2020 is the International Year of Plant Health but unfortunately, it has been overshadowed by Covid and has been under-reported. It is also ironic that in the year the industry highlights plant health Ireland had our first outbreak of Oak Processionary Moth (OPM) on imported Belgium Oak.  On December 12, 2019, European plant health laws came into operation with much stricter controls on traceability. Instead of only a few species requiring plant passports, the new regulations require every plant to be passported from the original grower to the end-user and these records must be held for three years. Other changes included the requirement for everyone involved in plant trade to register with the department and follow the new regulations. This includes, among others: online traders, local authorities and landscape designers who import plants. Prior to these regulations anyone could call up an overseas nursery, buy a truck full of plants and get them delivered directly to site with no plant health concerns. Yet despite these new laws, this is still happening. I am aware of at least two landscape designers who are not registered and continue to purchase plants directly from abroad; this is now a crime and puts our environment at risk. The proper implementation of the new regulations has cost nurseries money with the purchase of extra equipment, and requires on-going attention and labour. Nurseries are easy for the department to control but many other aspects of the plant trade are more difficult. I am not a Eurosceptic, but many of the challenges we face with plant health stem from the free trade within Europe. The earliest reference to Ash Dieback that I could find was in a report from a Teagasc delegate from a meeting in 2012 where it is clearly stated that by 2007 Germany were observing a serious increase in infections. Why did we not ban the importation of Ash there and then? The answer is we cannot unilaterally ban certain plants when the plant health organisation in the exporting country deems them to be healthy. At the time of our first importation of Ash Dieback, Fraxinus did not require a plant passport and with the massive demand in Europe during the boom for Ash, chaos ensued and infected plants from Eastern Europe found their way onto Irish roads and into Irish forests. TAKING THE INITIATIVE So, our first defence against plant pests and diseases rests in the hands of the inspectors of the exporting country. That’s reassuring. However, I will say if they are as thorough as our inspectors then we will have nothing to worry about. At present we have OPM pheromone traps on the nursery put up by the department, which is initiative-taking and reassuring for our customers. Ireland is deemed to be a Protected Zone for OPM and therefore there are extremely strict rules concerning the importation of Oak. A quick read of the new EU rules almost requires them to be grown in a vacuum in outer space. The cultural requirements are so extreme that both Holland and Germany suspended Oak exports to Ireland and the UK in September 2019, because they knew they could not satisfy the new regulations. This was the system working properly. So how then did we end up with OPM in a public park in South Dublin? Because not one other EU member state followed the lead of Holland and Germany, claiming therefore that their Oak was OPM-free. This is a moth native to southern Europe on the march north due to global warming with no regard for borders and known to be widespread in northern Europe. Belgium was one such country and indeed the source of the infected Oak in Dublin. While most Irish nurseries stopped importing Oak after the unilateral move by Holland and Germany it is obvious that some didn’t, leaving the door open to OPM. You may also ask why a local authority parks department did not stop the use of imported Oak. Simply, they cannot due to EU laws regarding purchasing even though the Oak trees in question were available, at the time of tender, from Irish growers. There is no weighting given to Irish grown stock on any public supply tenders and this cannot change once we are in the EU. OPPORTUNITIES However, all private tenders for landscape plants, be they large or small, are not subject to such rules and offer a way to reduce imports and thus the risks associated with it. Some compromising will be needed as Irish growers can only produce so much and do not have infinite availability. But with some increased communication between Landscape Architects / Designers and the nurseries and a willingness to adapt the design to availability, we can reduce the dangers of importing more problems. Another problem that drives imports is the specification, sourcing and timing of commercial plant projects. If the nurseries were involved from the start of the project, not at the end when panic ensues, then almost all items needed can be grown in Ireland and not imported in a rush to finish. Other opportunities offered by the new regulations and our Protected Zone status depend greatly on keeping as many rampant European pests and diseases out of the country. Ireland is the only EU country with an OPM protected zone. This offers Irish growers’ great access to the UK market for clean Oak from Ireland. Indiscriminate importing from other European countries put this at risk and I would ask all importers to look for an Irish product first. Ireland is a protected zone against 22 horticultural pests and diseases, the highest in Europe, let’s not lose any more plants. In my lifetime, in trees alone, we have lost Ash, Chestnut, Sweet Chestnut, Elm and Japanese Larch to imported pests and disease. One significant trend worldwide, which has been noted in PHYTOFOR research, is the increasing number of invasive alien Phytophthora species being detected in natural habitats. Many of these pathogens are being brought into the country on infected plants and could represent a serious threat to Irish ecosystems in the near future. ✽ JOHN MURPHY is the owner and operator of Annaveigh Plants and is one of Ireland’s most experienced and respected nurserymen. For more information visit www.annaveigh.com |